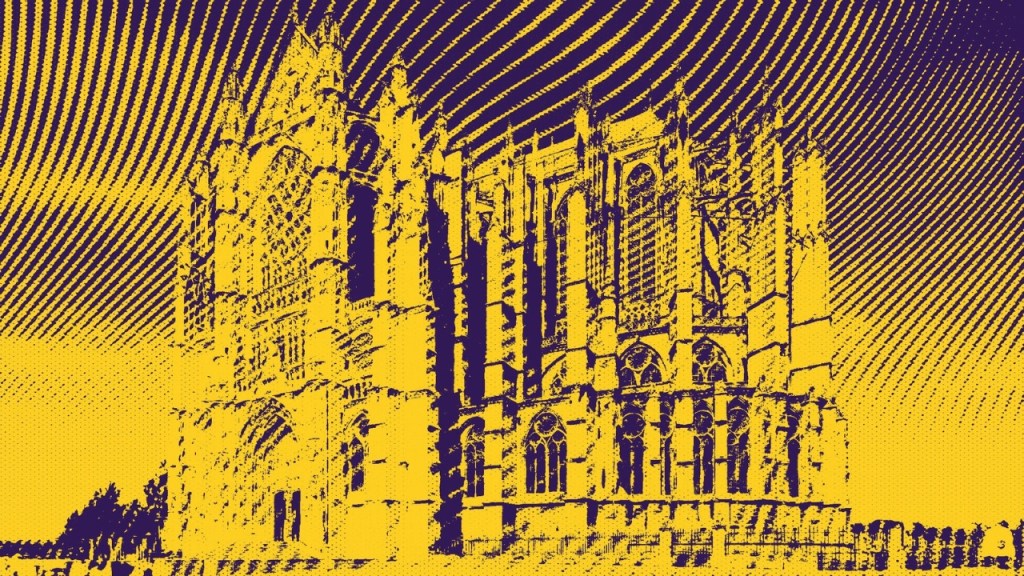

In northern France, the Cathedral of Beauvais rises as a “fragment of the impossible,” a structure that attempted to transcend the human condition through sheer verticality. Begun in 1225, its choir soared to an unprecedented 48.5 meters—the greatest elevation ever achieved by a stone vault in medieval Europe. However, this architectural ambition met a catastrophic limit on November 29, 1284, when part of the vaults collapsed, turning the summit of Gothic aspiration into its most visible wound.

A new study by Rubén Rodríguez Elizalde revisits this historic event through the lens of posthumanist thought. Rather than viewing the cathedral solely as a monument to human genius or error, the paper interprets it as an “architectural sympoiesis”—a collaborative process where human design, material behavior, and gravity act together. Drawing on the theories of Donna Haraway and Bruno Latour, the cathedral is defined as a “distributed assemblage of agencies” in which stone and geometry are active participants.

Quantitative analysis reveals that Beauvais was built at the very threshold of theoretical stability. With pier slenderness ratios of approximately 16:1 and safety factors reduced to a minimum, the structure was a “limit system” that prioritized ontological statements of light over conservative engineering. The study argues that the 1284 collapse was not simply a failure of calculation but a moment of “posthuman epistemology”—a form of learning where technical limitations and material responses converged to redefine construction knowledge.

Following the disaster, medieval builders did not abandon the project; they adapted by thickening piers and adding iron tie-rods, engaging in a continuous negotiation with the material. Ultimately, the study presents Beauvais not as a ruin, but as a “living machine of meaning”. It serves as a timeless lesson that true technical progress lies not in the domination of nature, but in understanding risk as an essential component of knowledge.

Leave a comment